Overview

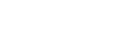

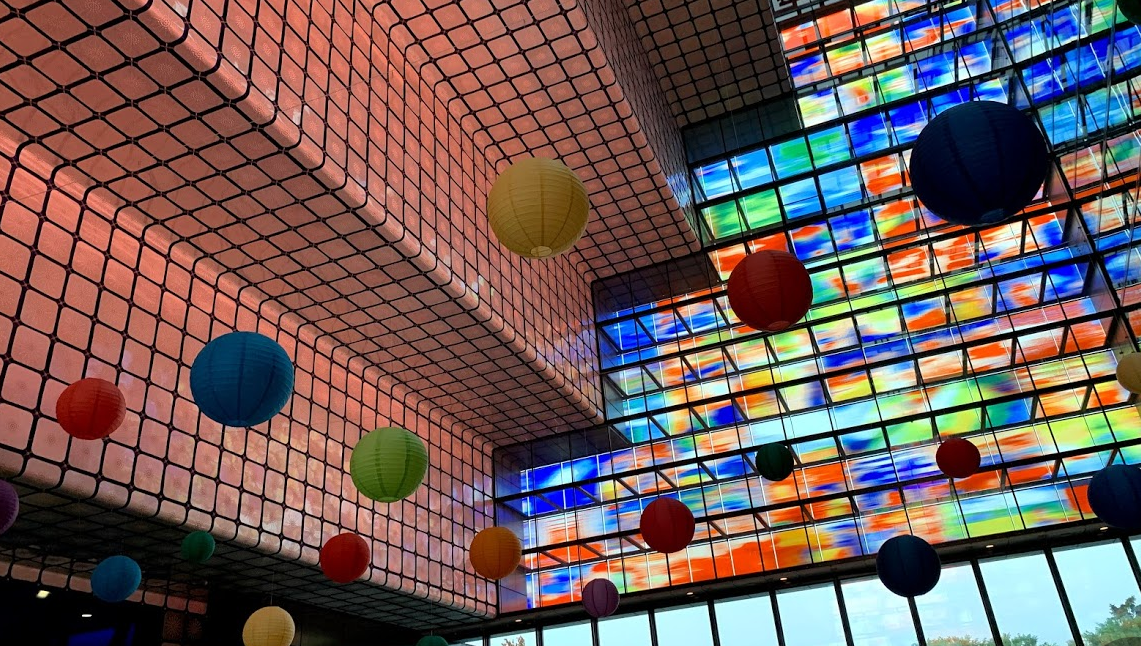

IASA 2019 marked the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives’ 50th anniversary. It was hosted by Beeld en Geluid, the Netherland’s Institute for Sound and Vision, in their bespoke digitisation and exhibition complex, situated approximately 30 minutes from Amsterdam within the Dutch Media Park, home to various national broadcasters and production companies.

The theme of this year’s conference was Imagine the Future, drawing presentations about new technologies and techniques relevant to the world of audiovisual archiving, across many fields, including: musical recordings; historic, literary, folkloric, and ethnological sound documents; theatre productions; oral history interviews; news and broadcast materials; bio-acoustics; environmental and medical sounds; linguistic and dialect recordings; as well as recordings for forensic purposes.

IASA

The theme of “Imagine the Future” made way for many talks regarding artificial intelligence and process automation. Given the archival spin of talks about these topics, it made for an interesting look into the possibilities for larer organisations to enhance discoverability of their content, and for increasing the speed of the transfer process for less problematic materials (such as commercial video tapes or compact audio cassettes). While most of the discussion brought about by this theme is not currently relevant to the digitisation focus of the National Museum – Czech Museum of Music, it will no doubt become an essential time- and cost-saving element as digitisation efforts are expanded in the future, offering automatic annotation, detection of non-speech, non-music sound events, environmental descriptions and much more.

More immediately pertinent presentations included the presentation of IIIF for AV. The International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) has been developed over recent years to provide a new way to standardise access methods for images, with built-in support for time-based media such as film and audio. Using the IIIF Presentation 3 API, interoperability of AV collections is enhanced, allowing for content annotation and more specific, user-focused presentation of audiovisual material that will no doubt become a minimum expectation for cultural heritage institutions in future.

While looking to the future, the past cannot be ignored. The issue of obsolescence is a very real threat to audio collections. With materials degrading on the shelves of cultural heritage institutions world-wide, the need for appropriate playback technology is growing. As machines become harder to source, the cost of preservation grows, putting more pressure on institutions to take ideas from industrial manufacturing processes to increase efficiency of digitisation. The world’s leading AV preservation programmes have all taken this to heart, transferring multiple carriers in parallel and investing in robust quality control processes to optimise their throughput. To preserve Czech audiovisual heritage, a dedicated mass-digitisation programme that can be sustained for the long term is a necessity.

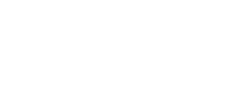

Alongside sharing methods and recommendations, IASA offers a chance for research departments to showcase their latest technologies. This saw presentations by Nick Bergh, creator of the Endpoint Cylinder Playback System – a device which can transfer all types of phonograph cylinder (the oldest form of audio carrier), recently purchased by the NAKI New Phonograph project – who demonstrated enhancements to the system which allow for high-quality transfers of magnetic belts – a rare type of carrier which uses magnetised iron filaments to record and play audio. He also unveiled a new device for wire format audio, which provides a means to regulate tension and avoid the common and disastrous problem of wire breakage. Bergh followed this talk with a presentation at JTS covering the latest features of the cylinder playback system.

The community of IASA is largely open to being self-critical. As such, a presentation by IASA’s president Toby Seay, titled Higher than 96KHz: A case for magnetic tape, brought into question IASA’s TC-04 guidelines which recommend an upper sampling rate limit of 96kHz. Seay demonstrated the loss of high frequencies – which spread well above the 20kHz threshold, often into the high 30 or 40 kHz range – in transfers which follow this recommendation. For archival practice, these inaudible frequencies can still have an impact on the sound as their omission results in audible artefacts.

Other talks included the application of software development techniques (ie, concepts such as scrum, sprints, huddles, tribes, etc.) in the archival sector. Using such techniques in the project management lends itself well to organising the digitisation of various collections, wherein the assorted documents and desired outcomes may vary greatly from previous collections and an agile approach is therefore most suitable. This is something we are currently investigating in the New Phonograph project and see benefit in adopting, albeit not in a strict model – it should be noted that this talk also made exceptions where techniques were modified to fit the needs of the archival space. Another talk focused on the idea of perfection, where the demands of digitisation only allow some degree of perfection to ever be achieved, and that, philosophically, one might be better off lowering standards to ‘good’ rather than ‘perfect’, for the purposes of research and preservation.

Finally, there were talks which covered novel techniques for error checking, presented by Cedar audio, a well-respected development firm at the forefront of audio restoration, as well as new types of long-term storage, such as Piql’s paper tape that has been used by Cesky rozhlas to preserve AV documents from the Prague Spring, which now sit in an arctic vault with the potential to survive for hundreds or thousands of years. Alongside this, the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA) of Australia are working on DNA storage, which is expected to become a viable means of data storage within 5-10 years. Copyright was also much discussed, with one talk regarding the EU copyright directive which is due approval and allows cultural heritage institutions to obtain licenses from representative organisations to use these out of commerce works for non-commercial purposes, with the licence extendable to similar out of commerce works which are not represented by the organisation. Furthermore, the Directive will also allow cultural heritage institutions to make copies available online of these works for non-commercial purposes without a license, where there is no representative organisation to obtain a license from.

Joint Technical Symposium

Where IASA 2019 was intended to deal with a broader selection of topics, the Joint Technical Symposium (JTS), is more focused on the scientific and technical matters behind audiovisual preservation. Where IASA happened to have talks about the role of AI in archives, JTS opened with a keynote on ‘what the archive can do for AI’, reminding us that we have a role to play in the provision of annotated data for machine learning purposes. This largely stems from the problem of a programmer choosing may describe kilts, robes, thawbs, gowns, etc. as “dresses”, to cater to the AI’s limited ability to discern between them. In the same situation, an archivist would be inclined to describe each in its cultural and physical context, resulting in high-quality annotated data that will go a long way to improving the overall capabilities of the AI system.

As a prominent figure in the world of audiovisual archiving, George Blood’s presentation took a very direct approach in trying to answer some of the frequently asked but never conclusively answered questions of the AV world. This was broken down into 9 questions, from how long a diamond stylus might last, or whether cleaning tape too many times is detrimental, to whether we can continue drilling holes in magnetic shielding to make azimuth access more convenient, and many more. While his team’s approach was necessarily rough and sample sizes were perhaps smaller than ideal, in most cases it provided evidence that can be taken as conclusive, finally debunking some myths regarding the practices of digitisation and archiving.

While Nick Bergh, creator of the endpoint cylinder player, demonstrated the latest machine (a recent addition to the digitisation studio of the National Mueum – Czech Museum of Music) in his morning lecture, another specialised machine was also on display during IASA and JTS – Saphir, an entirely contactless solution for playback of delaminated or otherwise heavily damaged lacquer discs. Developed by the French institut national de l’audiovisuel (INA), we presented two damage Thorens records from the collection of the National Theatre, which were successfully digitised using the Saphir system. Another 37 sides from 21 records were also digitised during the course of the conference, flown in to the Netherlands by attendees from across the world. While the machine is still only a prototype, it could, along with its underlying computer code, offer a novel solution for transferring otherwise unsalvageable content for a reasonable price.

A largely undiscussed issue within archives is what is happening to digital files at the bit-level. With recent experience in criminal forensics, Bert Lyons of AVPreserve gave his presentation alongside Dan Fischer of PortalMedia, about the data which comprises the content we hold in our digital repositories. While checksums and fixity checks are used by many institutions, there is a level of digital forensics which can be employed to the benefit of the archive. This presupposes a degree of understanding of computer science within archive staff, which is often not the case. The main benefit of binary-level analysis of files is that it can be used to identify equipment, leftover traces of any processing, detect tampering, and inform how file repair or reconstruction is approached.

Data is central to archiving and also central to JTS. Indiana University’s (IU) Brian Wheeler, who met with the Novy Fonograf team in 2018, spoke about the IU Media Digitization Preservation Initiative, describing the challenges and redesigns met along the way to having now digitised 320,000 objects. This included how to deal with scalability – now handling upwards of 35 Terabytes daily – and how the process would look if Wheeler were given a chance to redesign it, with some choice words about the decision to use tape as primary storage, and a bittersweet relationship with PERL. His presentation was followed by INA’s Etienne Marchaud, who focused on the open source software which has been implemented into INA’s workflow, with a useful breakdown of how well they perform and how easily they can be adopted by institutions – depending, of course, on the staff’s CS knowledge.

Automation was again a popular theme at JTS, with the idea of auto-populating descriptive metadata being of particular interest. A number of presentations, such as the one delivered by Karen Cariani & James Pustejovsky, brought to focus the added value of moving beyond simple transcription of audio, but also extracting data from credits which roll at the end of a programme. Other features of their open-source tool “include video clean-up (removing bars and tone), categorization of different audio elements (music, applause, external sounds), distinguishing language types, categorizing scene types, and creating named entities that are linked to existing authority records.” Another development in this field comes from a partnership between AV Preserve, Indiana University and the University of Texas funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, to perform mass description of audiovisual content through automated mechanisms and human labor to generate and manage metadata at scale for libraries and archives.